Kinvara

A Seaport Town in the West of Ireland

Towns are a late introduction to Ireland. Unlike Britain, which was an important and thriving out post of the Roman Empire for almost four hundred years, Ireland was largely unaffected by Rome, with its military and economic strategy of establishing towns and cities with well-built roads to connect them.

Because of the very different culture of Celtic Ireland, a society that lacked both the centralizing motive and the political institutions to bring it about, the only clearly recognizable analogy to what historians and sociologists would recognize as towns are the settlements that grew up around monastic sites like Kells and Downpatrick. But even these are probably no earlier than the late ninth and tenth centuries. Likewise with the settlements, which were genuine towns, established at around the same date by the Vikings, especially along the cast and southeast coasts.

With the arrival of the Normans in the twelfth century, however, town building got underway on a scale both extensive and well-organized, leading over the next two centuries to the creation of large and legally chartered towns, similar to those in England. To this category belong such cities as Wexford, Waterford and, in the West, Galway.

These Norman towns and cities were deliberately designed as bulwarks against the threats, potential or actual, posed by the native Irish. In addition they were important instruments in the colonization of a country still largely in the hands of its native population. Galway, where ‘neither O nor Mac’, i.e. the native inhabitants, were encouraged to visit and certainly not to take up residence, is typical of these settlements that stood like islands in the midst of an ‘uncivilized’ and antagonistic people.

In the topsy-turvy world of the colonizer and the colonized, the former saw themselves as the legitimate authority based on their rights of conquest and, as the years passed, increasing ownership of the land, while the latter were regarded by their new masters as a subservient people, largely because rights were equated with property and so those without any had few, if any, rights.

This situation with respect to colonizer and colonized hardened after the Parliamentarian and Williamite wars of the seventeenth century. The only major innovation in the following century was the increasing tendency of eighteenth century ‘improving’ landlords – the type Arthur Young admired – to build towns on their estates. Though the chief motive was undoubtedly economic, the enlightened landlords who practiced town-building also acted under the more praiseworthy liberal ideal of their class having a ‘duty’ to contribute to society’s betterment.

However, it is the nineteenth century that witnessed the greatest growth of towns and villages throughout the country. The French Wars of the last decade of the eighteenth century and the first decade and a half of the nineteenth century had a major impact on the economic growth of the country.

As a subject-state (even more so after the Act of Union in 1801) of the only nation to hold out in the wake of Napoleon’s military sweep of Europe, Ireland was expected to supply men and materials for the war effort. As is always the case, war provided economic opportunities for those poised to take advantage of them. Another factor that had an important effect on the growth of towns in the nineteenth century was Catholic Emancipation, which led to church-building on a large scale, followed closely or accompanied by the arrival of teaching orders like the Sisters of Mercy and the Presentation nuns.

With religious emancipation began a slow but steady economic emancipation that is most clearly seen in the growth of the small merchant class and the town or village shopkeeper. Gradually and then rapidly, the nineteenth century witnessed the evolution of the town as the new social, cultural, educational and economic focus of a still predominantly rural society. Any social fact requires a reason for its existence; by the end of the nineteenth century, there were plenty of reasons – economic, political, social – to explain the central importance that towns had in Ireland.

Tracing the history of a town like Kinvara, at least before the late eighteenth and nineteenths centuries, is a difficult task. Not only are there very few records that date before this period, but Kinvara’s isolated position means that few, if any, English or continental travelers of the sort who certainly did visit other more accessible parts of Ireland in the earlier centuries, left any account of what they found. When, for example, road-building on a large scale was undertaken in the late eighteenth century, and the earliest road maps were published, Kinvara simply did not feature because it was not on a main thoroughfare as was, for example, a small town such as Ardrahan, which was on the Gort to Galway road.

Kinvara, in Irish, is ceann mhara, which means ‘head of the sea’, a designation that perfectly describes the situation of this South Galway town at the head of the narrow inlet of Galway Bay that is known, not surprisingly, as Kinvara Bay.

Yet if this is the name that has become established (without the addition of a second letter ‘r’, which derives from English orthography and is still, unfortunately, employed on both national and county maps and road signs), in the earliest documentation we find such other forms as ‘Kenmara’, ‘Kynmara’ and ‘Kyndiura’.

The ancient name of the parish is Killoveragh and on the earliest maps to show the area we find, for example, on Speed’s 1676 map and Sir William Petty’s 1685 map we find the name ‘Killouarow’. Killoveragh is an English transliteration of the Irish Cill Ui Fiachra. Fiachra was the common and perhaps legendary ancestor of the tribe, clan or tuath known as Aidhne, one of the two sons, again probably legendary, of Fiachra. And from ‘Aidhne’ comes the name ‘Hynes’, which we find intimately associated with the Kinvara area up to present times.

The only dispute concerns the Irish ‘cill’; is it to be taken as ‘coil’, which means wood’, or as ‘cill’, a prefix which means ‘church’. It is impossible to say for certain, as both arguments have weight; woods had a special and probably sacred significance for the Celts, and there is evidence that Irish chieftains were inaugurated beneath a sacred tree. The village of Roevehagh, near Clarenbridge, takes its name from a sacred ash under which the chieftains of Ui Fiachra Aidhne assumed their positions.

On the other hand, the Kinvara area contains the remains of many early churches, or the ruins of churches that probably replace much earlier foundations. Notably, there are the ruins of what the 19th century scholar John O’Donovan described as a church 500 years old that most likely “occupies the site of a primitive Irish church” dedicated to St. Coman, a saint of the 5th century. Fahy, in The History and Antiquities of the Diocese of Kilmacduagh, states that “in the long past, none but the recognized and leading representatives of the Hy Fiachrach tribes…were allowed the privilege of interment within the sacred precincts or the church of Cil Ua Fiachrach at Kinvara.” From the way Fahy describes it, we can see what side of the argument he favors. All we can say is neither argument can be conclusively proved.

Early references to Kinvara fall into two categories: those found in the delightful but scarcely reliable ‘God’s plenty’ of legend; and those from the more sober but also more reliable Irish chronological annals such as the Annals of the Four Masters, lists of land holdings and castle occupation, and records of ecclesiastical visitations in the medieval period.

Of the first, it is pleasant to encounter in the medieval Book of Lecan an account of a battle fought at Kinvara by the redoubtable Fionn Mac Cumhaill; we learn that Fionn “defeated the chieftain Uinche in a battle at Ceann Mara, now known as Kinvara, on the Bay of Galway.” Again, the eleventh century ‘Voyage of the Ui Chorra’, an example of a popular Irish genre known as Immrama, which tell of fantastic voyages, replete with magic and otherworldly incidents, we have the story of a trio of marauding brothers who wreck havoc against the Christian churches of Connacht but who, after destroying “the church of the holy old man., Coman of Kinvara”, discover they have gone one church too far. Full of remorse, the penitent brothers rebuild the church and receive baptism at the hand of St. Coman. Although it is impossible to date this tale, it is of interest because it confirms the importance of this particular church for the author, who was probably writing in the early medieval period and possibly even preserving an old tradition of the church’s destruction at the hands of sea marauders, something we know from the Annals of the Four Masters to have been associated with the Viking raids of the 9th century to have been of frequent occurrence in the South Galway area

The almost complete darkness that covers Kinvara during these centuries is suddenly illuminated in another medieval Irish chronicle which John O’Donovan translated as The Manners and Customs of Hy Fiachrach, Here we find an account of St. Colman Mac Duagh, a saint of the late 6th and early 7th centuries who was born at Kiltartan, about ten miles from Kinvara, and who is associated with the foundation of the monastic site of Kilmacduagh, near Gort. Said to be “of the race of Fiachra’, he is also associated with Guaire, a well-documented chieftain of Ui Fiachrach Aidhe whose ‘white-sheeted fort’ has been identified with the overgrown promontory fort immediately to the east of Dun Guaire Castle. Both saint and chieftain were the focus of a number of colorful legends which, if hardly historical, certainly show the importance of both men for later generations.

One of the earliest names linked to Kinvara is that of another cleric, Ailbhe of Kinvara, whose death is recorded in the Annals of the Four Masters in 814. This chronicle, compiled in the 17th century but containing earlier material of varying degrees of reliability, provides no other information apart his name, the place he was most closely associated with, and the date of his death. What precisely was his significance is a mystery, but it is probable he was of some importance or else his death would have hardly been so carefully noted.

During the 12th and 13th centuries what few records there are record a seemingly endless pattern of inter-tribal warfare and during this confused and confusing period we catch occasional glimpses of Kinvara, especially as it lay on the edge of Ui Fiachrach Aidhne territory, adjoining the extensive Burren tuath of the O’Briens, and would very likely have witnessed the back-and-forth traffic of the different armies.

By 1177 the Normans, under William de Burgo, who had received a grant of the entire province of Connaeht from his father-in-law, Henry II, made their first appearance. Typifying the pattern that was to end with the total collapse of native resistance and the end of Gaelic Ireland, leading de Burgo on this first incursion was Murrough O’Connor, son of the country’s last legitimate High King, Rory O’Connor. For his treachery, the king had his son blinded, only to discover that another son was engaged in a plot against him. Fleeing to the protection of the chieftains of Aidhne, the unhappy ruler retired to the Abbey of Cong, and after his death in 1198 his remains were taken to the traditional burial site of Clonmacnoise.

By the early years of the 14th century Richard de Burgo had made himself master of the extensive territory that was to be known as Clanrickard, and after the ‘Red Earl’s’ death in 1326, junior members of the de Burgo family, rather than see these lands revert to the Crown, seized and held them.

References to Kinvara during the several centuries that saw the de Burgo conquest of Connacht concern ecclesiastical appointments as well as land ownership of the O’Heyne chieftains whose several castles were close to Kinvara.

From Papal records we learn that the incumbent of the parish of Kinvara in 1407 was Nicholas O’Dubghilla, who was also a canon of Kilmacduagh, the Cathedral church of the bishop, as well as being vicar of Ardrahan. In 1423 the vicar was Donatus O’Leayn; in 1441 Denis O’Dubgilla held this office; in 1450 David Valens; and in 1502 Roger de Burgo.

Between 1565 and 1567 Christopher Bodkin, Bishop of Kilmacduagh and also Tuam, conducted an episcopal Visitation of the two dioceses, and from the manuscript we learn that Arthur Lynch held the living of Kymara.

Turning to the O’Heyne residences, from a manuscript of c. 1574 listing castles, their owners and their locations. The purpose of the list seems to have been to assist the Lord Deputy of Ireland at that time, Sir Henry Sidney, in planning the division of Connacht into the administrative units we know today as baronies. A barony seems roughly to have corresponded to the territory of a particular chieftain who went through the legal process of submission to the Crown.; in return, he would receive his territory back again but now no longer as its hereditary chieftain but as the feudal subject of the Crown. This division, known as the Composition of Connacht, was carried through by Sir John Perrot in 1585; although few could have guessed it at the time, the result was the gradual destruction of the ancient Irish clan system.

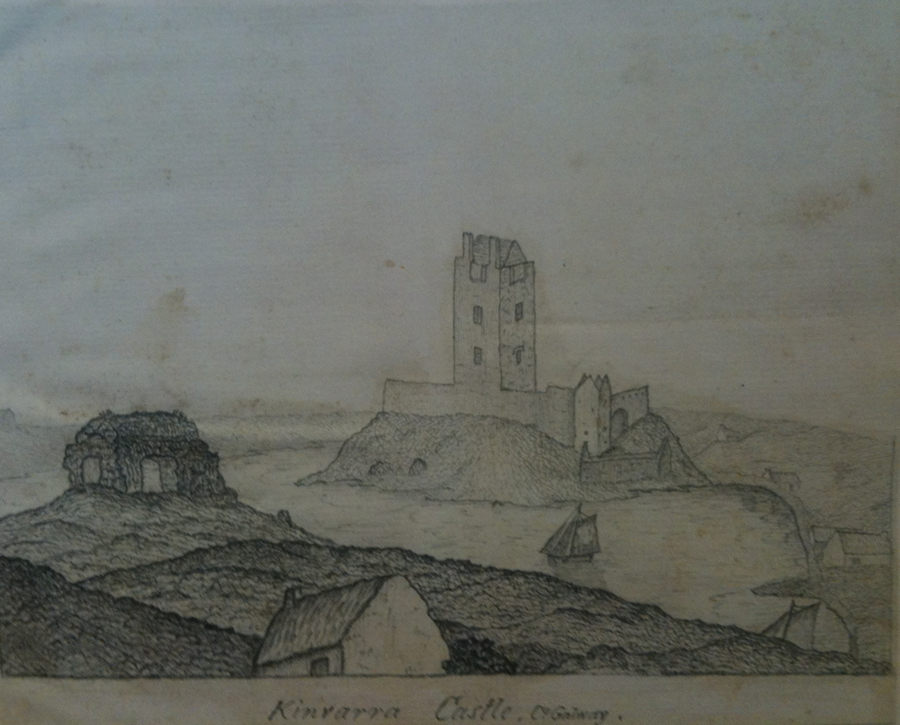

From the castle list for the barony of Kiltaraght or Kiltartan, we learn that Owen Mantagh Ohein was chieftain and that his principle residence was his castle at Kynmare or Kinvara However, we find another reference to fferigh Oheyn who lived at Dungwory, which is clearly Dunguaire. It has been suggested that the castle at Kinvara actually stood on the site of present-day Delamain Lodge.

In the 1585 Indenture, or contract, between Sir John Perrot and Ulick de Burgo, Earl of Clanrickard, it is stated that Oene Mantagh O’Heine lived at ‘Downgorye’. But three years later, Dunguaire was in the possession of Hugh Boyc O Heine, son and heir of Owen, according to a grant dated 23rd July 1588.

By the end of the 16th century the fortunes of the O’Heynes were steadily declining. Through the submission process the traditional bonds between the chief and his people were fatally eroded, and by the end of the 17th century the O’Heyne or Hynes family are no more than respectable landowners among many others.

Interestingly, the tradition of the hereditary chief of the Ui Fiachrach was still alive when John O’Donovan was engaged in the field work for the first ordnance survey in 1837-9. In his notes on Kinvara, which included this learned scholar’s references from ancient Irish manuscripts, he mentions “O’Heyne of Ardrahan, who is commonly known in the County as “Heynes the Process Server’, who is “the representative of Guaire Aidhne and hereditary chief of all the Hy-Fiachrach of Kilmacduagh Diocese”.

O’Donovan also mentions John Heynes, who was at that time (c.1839) ‘the present representative of the branch of the family’ who lived in Corran rue Castle, which, O’Donovan informs us, ‘fell in the year 1755 at the very moment that the earthquake happened at Lisbon”. O’Donovan further informs us that members of this family also occupied ‘the castle of Ballybranaghan at Kinvara’. As we have noted earlier, this cannot be Dunguaire Castle, which is always referred to by this name. This is the castle that most probably occupied the present site of Delamaine Lodge which is in the townland of Ballybranigan.

In 1607, according to an inquisition, or investigation, taken at Loughrea, we find that Oliver Martyn, a member of one of the original Anglo-Norman ‘Tribal’ families of Galway, was living at Dunguaire, and it is possible that he rented the castle from the O’Heyne family. An interesting document in the British Public Record Office, dated at Westminster, Feb. 21, 1615, grants Oliver Martyn the right to hold a Saturday market at Kinvara. Such official grants often only regularized existing practice, so it is reasonable to assume that markets were being held at Kinvara for some time before this date. For this right to hold a market, Martyn paid the Earl of Clanrickard an annual sum of l0s. This was the beginning of the toll and customs system in Kinvara, which continued right up until the 1950s.

According to the Strafford Survey carried out in 1636, Dunguaire was held by the Earl of Clanrickard and it is possible that the Martyns leased it from him. At any rate, by 1642 we find Richard Martyn, who was also at this time Mayor of Galway, living in the castle* The Martyn ownership of Dunguaire Castle continued up until the early 20th century when Edward Martyn, one of the founder’s of the Abbey Theatre, sold it to Oliver St. John Gogarty. *(Among the Blake Family Records, there is a. document [No.110] that mentions Richard Martyn: “Bond given by Richard Martyn of Dungory in the county of Galway, Esq, to John Blake, Esq., Receaver-General (sic) of the Province of Conaght, to secure the repayment of £12 10 shillings. Attested under the hand and seal of the obligor. Dated April 24, 1647. Signed ‘Ri Martyne’.”)

The great events that dominated the 17th century in Ireland – the rebellion of 1641, the Parliamentarian war and the transplantation policy during the Protectorate, the Restoration, the Jacobite war and the subsequent confiscation of Catholic property and the imposition of the anti-Catholic penal legislation – can be seen as having an impact on the development of Kinvara.

Evidence of the continuing efforts to impose the Established Church of England in the diocese of Kilmacduagh) can be seen in the account of the 1615 document describing the ecclesiastical visitation of the Reformed bishop of Kilmacduagh and Clonfert, Roland Lynch.

Vicar of Kinvara in 1615 was Donaldus O Moynie (Donald O Mooney) who, is stated ‘serves the cure himself’, i.e., was a resident cleric, and that the value of the living, or position, was l0s. It is further stated that the church has been ‘repaired’. What church is referred to? It can only be the old parish church: now hidden behind the block of buildings extending south along the quay front and west up the incline of the main street. Donaldus O Moynie also was prebend (a term referring to the holder of an ecclesiastical office connected to a non-monastic cathedral bringing with it a certain revenue) of Kinvara, a position that was valued at 13s 44d.

Light is thrown on one of the chief questions to do with land holding in Kinvara, namely the glebe lands (see map) that cover an area of several acres on the north and south sides of the upper. Donaldus O Moynie as incumbent vicar (in the Church of Ireland a position roughly equivalent to a priest in the Roman Catholic Church) was entitled to receive from the Laity of his parish tithes, i.e. a tenth percentage of produce and or monies, to maintain himself and care for the fabric of the church. In addition a portion of land in the parish was given over to the vicar to either farm himself or rent to others who would pay him for its use When the Reformed Church of Ireland became the Established form of the Christian religion in Ireland, the system of glebe land was inherited from the displaced Roman Catholic Church.

After the end of the Parliamentarian war a process of property confiscation was applied to those who had supported the losing side. From the Book of Survey and Distribution for County Galway we see that by the terms of the Cromwellian redistribution of land the O’Heyne family were virtually dispossessed, their former property being assigned to various loyal supporters and soldiers of the Parliamentarian side

Among those on the losing Side was Robuck French, a Galway merchant who had his house property in the city confiscated. By a decree of final settlement dated 30th August 1656, allotted as a transplanted person he was assigned extensive portions of land from Balllindereen to Kinvara and Doorus, including the town of Kinvara itself. This was the beginning of a long association of the French family with Kinvara, continued into the early years of the 19th century by their de Basterot descendants.

The Penal Code was a body of laws enacted by the English Parliament during the first quarter of the 18th century. Although designed to make the practice and continued existence of the Catholic faith difficult, their main aim was to consolidate property in the hands of the Protestant landowners. Property meant power; so without property, it was argued, the Catholics, who were viewed with deep suspicion on account of their religion and their history of foreign involvements with Spain and France would gradually lose all power.

For landowners who were Catholic, like the Frenches, the law stating that if a son or other close relative conformed to the Established Church the estate would pass to them posed a serious threat, and we find the James French in 1762 conformed for this very reason.

Despite the harshness of the Penal Code, in an area like Kinvara where the chief landlord was himself a Catholic, religious life was never seriously disrupted. Fr. Turlough O’Heyne, who was ordained in 1674, was a native of Kinvara and from a number of documents we can see in him an example of the friendly relations that could exist even when Catholicism was legally constrained.

The old church in Kinvara was presumably in. the hands of the Established Church throughout this time. However, it may be questioned if it was still in use as a place of worship. Unfortunately we have no records at all of how many members of the Established Church resided in Kinvara in the 18th century, but it is not likely to have been very large and it is very probable that the church at Ardrahan, which became in the 18th century the main rural rectory of the Protestant diocese, was where Kinvara’s Protestant population attended service

The large and expanding Catholic population, on the other hand, was obliged to make other arrangements. From Report on the State Of Popery in Ireland in1731 we learn that a single priest served Kinvara, Doorus and Killina parishes. The Report further states that a chapel, erected sometime prior to the reign of George I, that today is only a heap of rubble in the older part of Mountcross Cemetery, was used for worship. As George I’s reign commenced in 1713, this means that there was no appreciable break in Roman Catholic worship despite the Penal Code.

Galway and the surrounding Bay areas, including Kinvara and Doorus (especially the former on account of its deep bay and numerous inlets like Crushoa Bay) were the center of an extensive wool smuggling operation throughout virtually the entire l8th century. After the Wool Acts of 1689 and 1698 excluded Galway from the privilege of being a wool-exporting port, with the sole exception of England, enterprising local gentry and merchants took matters into their own hands.

Quantities of wool would be shipped out of remote and isolated coves and in1ets by native sailors to places like Roundstone in Connemara where a French ship would anchor offshore, ready to receive the illegal cargoes. In return for the wool, enormous quantities of brandy, tobacco, French wines and teas – all of which could not legally be imported to Ireland – were brought into the country.

The revenue officers often knew the names of those involved, but as they needed the contraband cargo as proof and had no cruiser in Galway Bay to give chase to one of these illegal ships their position was a frustrating one. From the end of the18th century there are a number of vivid accounts to be found in contemporary newspapers describing the dramatic seizure of contraband goods.

For example, in the Connaught Journal of March 1st, 1792: ‘Last Tuesday, Messrs. Morrison and Mason, assisted by a party of the 17th Regiment of Foot, seized twenty-three bales of leaf tobacco at a village called Knoggery, and lodged the same in his Majesty’s stores.’ Knoggery is the village of Knockgarra in the peninsula of Doorus, which faces Galway Bay on its north side, the County Clare island of Aughinish, today joined to Doorus by a causeway, in the west, and on the east by secluded Crushoa Bay. The entire penisula was clearly an ideal location from which Kinvara’s smugglers could operate.

Evidence suggests that the Government constructed a small coast guard station on the quay in Kinvara in order to frustrate the activities of the smugglers. Local tradition has it that stones from this building were taken to build the four-storey building today known as the Old Plaid Shawl.

Delainaine Lodge, mentioned in the last section as possibly having been built from stones of the demolished Kinvara Castle in Ballybrannigan, would seem, from a convergence of evidence, to have been the home, from about 1760 to 1788, of a French Huguenot merchant named William Delmain. His son, James, had been born like William, in Dublin, and he married the only daughter of a Jarnac cognac firm called Ranson. James Delamain became a partner and the firm’s name was changed to Ranson & Delmain. Expanding rapidly during the decade 1770-80, the firm was the most important in the Cognac area by the end of the 18th century.

William Delamain’s local connections are strongly confirmed by the fact that his first wife was Hannah O’Shaughnessy, the daughter of Roger O’Shaughnessy, whose family were in the 16th century the most important Gaelic family in the Gort area.

The Delamain connection also includes a small chapel that stood, until it was most unfortunately demolished to make way for an abortive housing scheme, just behind the Pierhead Restaurant. Referred to by older local people as ‘The French Chapel’, it is described as having most definitely an ecclesiastical character. A cut and dressed stone doorway, almost nine feet high, was surmounted by a three-foot window described as ‘gothic’ in one account, and ‘obviously a church window’ in another. The most intriguing feature was the inscribed date of 1782 over the window

The Huguenots, French Protestants who fled their country in the late 16th century, were a highly industrious class of people, examples of whose delicate lace making and clothwork can be seen in such museums as the Victoria and Albert in London. It is also known that many of the Cognac families were or had Huguenot connections. So it is entirely possible that the legendary ‘Captain Delarnain’ local tradition recalls was accompanied during his residence in Kinvara by a small Huguenot community that may have had something to do with. the business he was engaged in, whether that happened to be legal, illegal or a combination of both.

As an interesting footnote to the Delamain presence in Kinvara, the Connaught Journal of March 25th, 1793, reports that an auction would be held on Thursday the 4th day of April’ of ‘a house pleasantly situated within a. few yards west of Kinvara with stabling for four horses and other offices’. The notice states that spacious eight-room house would make a most attractive ‘water lodge, there being a bathing house and strand close to the gate entering the lawn’. We know that William Delamain was back in Jarnac by 1788; it is, then, very possible that by 1793 William, who had been born in 1715, was dead, and that his son, James, settled now in Jarnac and running the business that would soon become simply ‘Delamain’, decided to sell the Kinvara house.

Certainly, however much smuggling there was, the French family, whose large house was the now-demolished ‘Prospect’ that stood in Doorus Demesne, were engaged in a profitable mercantile business that operated in the time-honored Galway trading triangle that begin in Galway Bay and whose two other angles were the Bordeaux region of Southern France and the Caribbean island of Santo Domingo.

In 1773 James French built the first quay of about 50 yards; in 1807, by which time the town of Kinvara had come into the possession of Richard Gregory of Coole, the quay was both lengthened and raised, and the following year a substantial further addition was made which converted it into a kind of dock. The final portion of today’s substantial quay was not constructed until 1904 It is also important to note that until the early years of the 20th century, Kinvara harbour was not a public but a private harbour, the tolls being paid to whoever at the time held the ground rents of the town,

In fact, not until the early decades of the 19th century was Kinvara made more accessible. In 1778 George Taylor and Andrew Skinner published Maps of the Roads of Ireland (surveyed 1777). On the map showing the Limerick to Galway road, the section that depicts that portion leading from Ardrahan to Galway, the beginning of what is described as the Kinvara Rd. branches off at the village of Ardrahan. At the point where the present-day road to Kinvara branches off at Kilcolgan, the only road shown is the present-day road that leads to Kilcolgan Castle, and further on to the St. George estate centered on Tyrone House. No road is shown below this one, where we should expect to find the present-day road that leads to Ballindereen and Kinvara.

The explanation is that at that date there was no such road, or if there was it was an undeveloped, poorly maintained trackway that was not developed until the early decades of the 19th century.

The principal road leading to Kinvara in the 17th century was what is today known as the Killina Road and on the 1st edition of the Ordnance Map (1837) as the Corrifin Road. The Northampton Road – referred to by older people as the ‘New Road’ – was not properly developed until the early part of the 19th century. It is necessary to keep these facts in mind if we are to understand the relative isolation of Kinvara in the 17th and 18th centuries, and to understand how the roadway of the sea was of much greater significance until at least the first third of the 19th century.

From the Records of the British Maritime Department we learn that the Kilcolgan-Kinvara road was only laid out in the second and third decades of the 19th century. In Kinvara this involved the construction of a long retaining wall, stretching from the harbour as far as Dunguaire Castle. The importance of this considerable engineering feat can be appreciated if we try to imagine the nature of the road covering this distance in the absence of this wall. In the absence of tarmacadam it would be little more than a track which, during times of heavy rainfall would have actually been dangerous to traverse, as even today it is a very narrow road, running close to the walls on the opposite side. With no barriers any heavy traffic, such as carts or wagons, would be in danger of sliding off onto the rocks below.

This activity at the seafront of the town, and the building at the same time of the substantial grain store that faces the quay, is an indication that what had probably been little more than a small fishing village throughout the 18th century was now seen in terms of its commercial possibilities by enterprising landlords like the Frenches and the Gregorys. Behind Tyrone House, near Kilcolgan, the St. George’s built their own pier and storage complex. In Doorus, the Lynches built their own quay, which, unfortunately, soon silted up and became unusable, while at the eastern end of Doorus the Board of Works built a solid pier that is still in use by local fishermen today.

The Connaught Journal noted in 1793 that the population of Kinvara parish comprised 2,000 people, What proportion of that number lived in the town is unknown but it is reasonable to assume that the late 18th century population was quite small. Ireland, especially in the West, was still overwhelmingly rural in outlook and orientation.

It is during the 19th century that we see the small village of Kinvara turn into a substantial town, with all the social accoutrements that distinguish the one from the other: a number of substantial two and three-storey houses, with proper streets to link them into the greater entity that is the town; large shops supplying many different items; a post office; a police station; a court house; warehouses and stores; mills; churches and schools; serviceable link roads with other towns; a variety of markets based on the variety of products grown or animals raised; in the case of a harbour-situated town like Kinvara, regular sea-borne trade; and a recognized distinction often, but not always, based on occupation – between town and country

Before we consider the development of Kinvara in the 19th century, it will be useful if we first of all consider this development in the centuries leading up to the last one. How did Kinvara develop? What is the significance of the 1615 market granted to Oliver Martyn? Is it possible to roughly date the oldest buildings and speculate on what Kinvara looked like in the Medieval period, in the late 17th and18th centuries? The attempt is worth making, even if we must admit most of it to be only informed guesswork.

a.) The physical setting of the town (see map for orientation)

The town lies on a rough northwest/southeast angle, clutching the western headland of Kinvara Bay, itself a long, narrow inlet of Galway Bay. Were there no town here, at high tide the bay waters would flow over the lower-lying land on the northwest, while on the southeast they would wash against a steeply rising hill.

Furthermore, as we have seen, the principal access road to Kinvara, until the construction of the retaining wall from the harbor as far as Dunguaire Castle, was not the present Kinvara-Kilcolgan road but the Corrifin (or Killina) road.

The main street of the town resembles a slighly-curving ridge extending westwards towards the comer of the Old Plaid Shaw. From this point the street starts to rise again, but more gradually, until it levels off near St Joseph’s Church

The main difference between the northern and southern sides of the ridge that defines the main thoroughfare is that the slope of the former is much steeper than that of the latter. Examination of the land on the southern side reveals a much more irregular configuration, with a very sharp dip and equally abrupt rise to the south, where the main street leaves the quay, but far less of one as it extends to the west.

b.) The development or the town up to the 19th century

The first building of any significance – and it may, in fact, have been the first structure of any kind – to be built in Kinvara was most likely the church that now is entirely closed in by the dwellings that extend to the west and the northwest. When the first church stood here – the present church is late medieval but there is every reason to believe that an earlier church was erected here perhaps as early as the 6th or 7th century. Positioned dramatically, it would have been the first sight to greet anyone traveling west along the bottom of the bay.

As mentioned earlier, about three-quarters of a mile to the east, on a piece of land jutting into the bay, is the probable site of the promontory fort identified with the 7th century chieftain Guaire, head of the Ui Fiachrach Aidhe and also king of Connacht.

The proximity of the fort to the church suggests an association of some kind between them, especially as it known that Irish chieftains who accepted Christianity often gave land for the construction of churches or monastic foundations, as Guaire is said to have done in the case of St. Colman, who is associated with the foundation of Kilmacduagh.

It is likely that the hill-top church site soon became a focus and that other structures were erected near to it. Of these, if they did indeed exist, there are no traces remaining. But the other feature of the town that probably dates from a relatively early period, perhaps the 11th or 12th century is the large section of land in the western part of the town known as the glebe.

As we have seen, the glebe land was allocated to the resident cleric to provide for his material welfare. Centuries later, when the Established Church of Ireland replaced, at least in terms of social and political terms, the Roman Catholic Church, the glebe land was simply taken over and allocated to the Church of Ireland incumbent for his needs.

We can only guess at the nature and extent of settlement around the church hill in the centuries leading up to the grant in 1615 allowing Oliver Martyn of Dunguaire Castle to hold a market. The only definite evidence comes from the presence of Dunguaire Castle itself, probably built in the early 16th century, the ruins of what was clearly another castle to the west of Dunguaire

There is also evidence that strongly suggests there was another castle close to the town, probably in the vicinity of the quay. In a list of castles in the Barony of Kiltartan, or Kiltaraght, a castle called Ballecastle, occupied by Mac Remon, or Mac Redmond Burke, is listed in for the parish of Kynmare, which is another form of Kinvara, or Cean Mhara. A castle near the quay, demolished by that time, is mentioned in Lewis’s Topographical Dictionary (1837). James Frost, in his History and Topography of Co. Clare to the beginning of the 19th century (1893), after mentioning the O’Heyne castle at Roo, or Reagh, which collapsed at the time of the Lisbon earthquake of 1755*, observes that “The present representative of the branch of the O’Heynes who lived in this castle and also in the castle of Ballybranagan at Kinvara), is a descendent of John Hynes”. Fahey, in his History and Antiquities of the Diocese of Kilmacduagh (1893), complements Frost; “…one of the fine old castles…was thrown down to supply building materials for the erection of the existing pier”. *(Editor’s note: Although not the strongest or most deadly earthquake in human history, the 1755 Lisbon earthquake’s impact, not only on Portugal but on all of Europe, was profound and lasting. Depictions of the earthquake in art and literature can be found in several European countries, and these were produced and reproduced for centuries following the event, which came to be known as “The Great Lisbon Earthquake.”

The earthquake began at 9:30 on November 1st, 1755, and was centered in the Atlantic Ocean, about 200 km WSW of Cape St. Vincent. The total duration of shaking lasted ten minutes and was comprised of three distinct jolts. Effects from the earthquake were far reaching. The worst damage occurred in the south-west of Portugal. Lisbon, the Portuguese capital, was the largest and the most important of the cities damaged. Severe shaking was felt in North Africa and there was heavy loss of life in Fez and Mequinez. Moderate damage was done in Algiers and in southwest Spain. Shaking was also felt in France, Switzerland, and Northern Italy. A devastating fire following the earthquake destroyed a large part of Lisbon, and a very strong tsunami caused heavy destruction along the coasts of Portugal, southwest Spain, and western Morocco.)

Certainly it is reasonable to assume that some of those who settled in the area of the future town were fishermen. Outside the walls of Galway city an ancient village known as Claddagh was comprised of people who made their living from the sea. The old name of the area to the east of the town of Kinvara, occupying roughly the coastal area extending as far as Delamaine Lodge, was also the Claddagh, and this name may preserve an equally ancient tradition.

There is an almost complete lack of information about Kinvara throughout most of the 18th century. How the town grew, and who were its inhabitants are questions, for the most part, without answers. However, the fact that there the present-day Kinvara-Kilcolgan road did not exist during the 17 and 18th centuries would certainly have contributed to the relative isolation of the small village.

The Frenches of Doorris Demesne continued as Kinvara’s landlords and it may be significant that no stories exist in the local folklore describing them as harsh masters. However, this absence may he equally well explained by assuming that they did not spend much time in the Kinvara locality. From early in the18th century, the Frenches appear to have spent much of their time at what was, in effect, their second home in Bordeaux, conducting their mercantile business.

James French conformed to the Established Church in 1762 in order to protect his Irish estate, but then decided to live mainly at his chateau at Chaillotlot near Paris. It was during his residence abroad that his daughter, Francis, married, in 1770, Bartholomew de Basterot, a member of the Parlement of Bordeaux.

The end of the 18th century is not altogether without information about the town of Kinvara, but it is very fragmented and any conclusions we draw from it must be tentative. We know, for example, that the first quay was built in 1773 by James French. We know that a small chapel, definitely identified as a Huguenot place of worship, stood in the area known as Claddagh, and that it bore a date of 1782. We know, further, that Delamain Lodge was up for auction in l793. From the Clonfert Index of Marriages, Wills and Administrations we learn the names of two people whose place of residence is given as Kinvara: Patrick Neilan (d. 1755), James Farrell (d. 1790). We also know that Col. Denis Daly of Raford was living in Dunguaire c. 1786; Daly’s wife, Anne, was the daughter of Malachy Donnellan, whose sister, Mabel, was the wife of James French of Doorus.

Another valuable source of information about pre-1800 Kinvara are the Papers of Dr. Nicholas Archdeacon, priest of Kinvara from 1798 to 1800, and bishop of Kilmacduagh and Kilfernora from 1800 to 1823.

Among the papers is an agreement entered into by Archdeacon on 25th June, 1797, by the terms of which he rented for the annual sum of £15.00 “the dwelling house, offices and yard, at the east end of the street of Kinvara …together with three acres of ground, adjoining Shessanagerby, the Glebe ground, and pound of Kinvara, commonly called by the name of Knockanelought”, for twenty-one years, from Jane Walker, otherwise Martyn, of Kinvara, Patrick Staunton, Esq.,, of Rue, and John. Farrell, Gent. of Kinvara. (The reference to “the dwelling house, offices and yard, at the east end of the street of Kinvaraa” is puzzling. Using the other locations in the rental agreement, it is possible to be quite precise about where the house stood. The townland of Shessinagirba is immediately adjacent to the glebe, and the old site of the animal pound was behind the present-day property known as the White House Bar, Knockanelought is not a townland but a place-name deriving from a physical feature; in this case. a small hill overlooking a marshy hollow that floods at Spring tides.

Now what is puzzling is the reference to the “east end of the street of Kinvara”. For today dwellings continue east as far as the wall surrounding the grounds or Seamount College. Is it possible that the original town developed on the upper slope of the ascending hill, and that there were no dwellings further east than west side of the town’s market square?

Supporting evidence for this suggestion may also be the grassed over road, elevated above the marshy hollow which, we are arguing, gave its name to Knockanelought, that a strong tradition says was the original road into and out of Kinvara. The course of this road, which leads directly off the market square, joins with the Killina or Corrifin road, about a quarter of a mile south of Kinvara. Probably there was no road at the bottom of the hill until the earliest portion of the quay was constructed. The land here is very low, and it is easy to imagine it would have been subject to flooding before the quay was built. Confirmation of this suggestion came about at the time of the ‘Big Tide’ that followed hurricane Debbie in the early 1960’s, when local people recall that the flood waters rose as high as Shaughaessy’s Drapery Store.

Continuing with our suggestion. we may imagine that once the threat of tidal flooding was removed, a road closer to the quay would have been more convenient for waggons and carts transporting goods to and from the interior of South Galway. At that point the old road would have starred falling into disuse, as the focus of the town shifted from the upper to the lower part of the growing town.

To sum up, there are good reasons for suggesting that the description of the property Archdeacon rented as being “at the east end of the town of Kinvara”, is accurate. This also means that the buildings that extend from the top or the eastern side of the market square were built somewhat later. Perhaps the buildings that extend eastwards at the junction of the present road 1eading south were also built later)

The significance of this matter-of-fact rental agreement lies in the fact that. it gives us the very first reference to a dwelling house and a street in Kinvara that we possess. It may not seem like much, but from it we can deduce that there was a roadway that was known as a ‘street’, a term that only has meaning in relation to a town. Furthermore, the description of the property suggests it was a substantial dwelling, with outbuildings, from which we can imply others of a similar kind. Finally, we have a reference to a pound for wandering animals, which, again, suggests a purpose-built structure of some kind. In other words, those living in the town of Kinvara took care to ensure that wanderings animals were not allowed to roam at will through the street (or streets).

John Farrell, described as a Gentleman of Kinvara – a term that implied both social status and property ownership, is interesting also. For in the Connaught Journal of December 1st, 1795, there is an obituary notice that reads: “A few days ago departed this life at Kinvara, in the county, greatly and deservedly regretted by her friends and acquaintances, Mrs. Eleanor O Farrell, wife of John O Farrell of Kinvara aforesaid.” Clearly, this was the wife of the Gentleman who is mentioned in the Archdeacon agreement.

From all of the above it is possible to state that at least by the end of the 18th century there was a town of some size, containing both several substantial dwelling houses and probably a small fishing village along the Claddagh, among which was also a small Huguenot chapel no doubt erected for the small Huguenot community that was attached to the residence of the Huguenot merchant, William Delamain, in some way.

Overlooking the town, and probably built around this same time, was Seamount House, the residence of a branch of the wealthy Butler family, whose principal residence was at Bunahow, South of Kinvara in County Clare. It is also possible that a coast guard station stood near the quay, perhaps partially built from the stone from the demolished castle of Kinvara. The town itself was still probably quite small. The First official census conducted in 1823 lists 64 houses in the town; twenty-three years earlier the number was probably much smaller.

Sometime before the end of the 18th century James French, who had been living in some style at Chaillot, his Chateau near Paris, and obviously running into financial difficulties, decided to sell a part on of his large estate of Doorus and Kinvara. The buyer was Robert Gregory of Coole, who thus became the new landlord of the town of Kinvara. As French’s great-great grandson, Florimond, Comte de Basterot, ironically commented in his autobiography, “In this way, the splendours of Chaillot were financed by a sale in Kinvara”.

While James French had been very largely an absentee landlord, Robert Gregory was an enterprising man, who, in addition to his Coole and Kinvara estates, went onto acquire another large estate beside Lough Corrib, with the result that he became one of the largest landowners in. County Galway.

Robert Gregory left his property to his second son Richard, instead of his eldest son, Robert, who had demonstrated by his addiction to gambling his unfitness to be entrusted with his father’s carefully built-up Irish estates. Richard Gregory was imbued with the ‘improving’ spirit of many late 18th and 19th century landlords and it would seem that he quickly realized the commercial potential of his Kinvara property, with its well protected harbour and the fertile agricultural land surrounding it.

Richard almost immediately set to work to improve the town of Kinvara. He made substantial improvements to the pier in 1807 and 1808, and it was he who also probably built the large grain store that faces the quay. According to Lewis’ Topographical Dictionary (1837), some of the stone used was taken from the ruined Kinvara Castle near the quay and he may also have demolished the abandoned coast guard station situated in the same area.

There is nothing to suggest that any of the present buildings in the town date to much earlier than the late 18th century, although it is possible that some of the older buildings, especially those on the south side of the town, may contain older portions reused and modified in the 19th century.

The most puzzling section of the lower town is the row of two and three-storey buildings that extend from Shaughnessy’s Drapery Shop to the corner building where Sara’s Restaurant now is. For these buildings, which give the strong impression of having been built at the same time (with one exception: the building now occupied by Mrs. Agnes Lynch is not shown on the 1839 ordnance survey map), are constructed on the lower portion of the hill surmounted by the medieval church, which itself is surrounded on all sides by the old cemetery.

This is quite extraordinary. Graveyards have always enjoyed a particular sanctity in the Irish imagination, and their desecration regarded with peculiar horror. Yet when the steeply rising main street was being prepared for the installation of water and sewer mains and road tarring in the 1930s, workmen unearthed a large number of human remains, demonstrating that the ancient graveyard extended at least this fan. When it is realized that the back windows of some of the existing houses on the northwestern side of the street overlook headstones that are so close they almost block the view, it is undeniable that the houses themselves have been built on a graveyard.

These houses, as we have stated, are clearly shown on the 1839 ordnance survey map, which means they were built some years before that date. Furthermore, from the evidence of headstones in this graveyard burials continued to take place here until at least the second decade of the 20th century (the most recent headstone is dated 1913). In 1866 Fr. Francis Arthur, P.P., wrote to Lord Cough, Chairman of the Gort Union, that the efforts of public authorities to close the graveyard to further burials was arousing fierce opposition.

Lord Cough’s reply paints a vivid and rather horrific picture of the scene outside the back windows of those whose houses were built here. The Board of Guardians, he informs Fr. Arthur, thought their decision was necessary as “the ground reaches up to within six feet of the second storey of the houses in the principal street”. Many, he continued, were obliged to board up their windows to keep out the effluvia arising from the bodies buried there because the bones and skulls were almost falling in the windows still left open. There was not, he added, six inches of earth in any part of the graveyard available for burying coffins, there being nothing but loose stones and the remains of former graves.

After further protests it was decided not to insist on the complete closure of the graveyard. Besides the 1913 burial, this author has it on good authority that a few burials continued up until about thirty years ago.

We are forced to conclude that these substantial houses, resting on the slopes of the graveyard hill, were probably constructed during the period when either Richard or his son, Robert (the father of Sir William Gregory, husband of Lady Augusta Persse), were landlords of the town of Kinvara How this was allowed to happen, and why there was, seemingly, no opposition to it are questions that elude any certain answers,

With the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 the mini-boom that had resulted from the constant demand for wool, cloth, timber and grain came to an abrupt end. Wide-spread distress replaced moderate prosperity and, as landlords also felt the financial pinch, those who failed to meet rent demand were evicted Twice in these post-war years the potato crop failed, in 1817 and 1821 – an ominous foreshadowing of what over-reliance on this single, easily grown crop, was capable of doing in rural Ireland.

Secret societies like the Terry Alts in Clare launched a general and only vaguely thought-out attack on landowners. From the Connanght Journal of April 21st, 1831 we read; “Committed to the County Jail this day, John Hynes, Michael Staunton, Stephen MeTigue, John Mulcahy, Matthew Winkle, Martin Dillane, Joseph Sheehan and John Douglas, all charged on oath with assembling in arms with many others, on the night of 3 st of March last, and burgluriously breaking open the house of John Burke, of Duras, and administering an illegal oath – and also with having on said night broke open the house of James Basterot of Duras and forcibly taking thereout one gun, the property of said James Basterot.” It is not surprising that the British 28th Regiment were based at Corrunrue in these years, nor that a garrison of soldiers was based in Dunguaire Castle in 1828.

In 1821 the first comprehensive census was conducted throughout Ireland, allowing us our first accurate picture of the population of Kinvara. We learn that the town contained 64 houses and 385 inhabitants. In 1839, Lewis’ Topographical Dictionary reported there were 824 inhabitants in the town, an increase of more than double the population in only sixteen years.

Lewis is also extremely valuable is giving us an insight into the economic situation of the town. We are told that the parish of Kinvara comprises 6114 statute acres, is moderately well cultivated, and produces excellent wheat. Seaweed, we learn, is used as a fertiliser, and limestone for building is abundant. The local Post Office was opened in 1833 as a Sub-Office to Ardrahan, and John Burke, who was also one of the Tithe Commissioners in 1826, was the first postmaster. There was also a police station in the town.

Markets were held on Wednesdays and Fridays at which ‘great quantities of corn are sold’, and fairs were held on May 18th and October 17th, ‘principally for the sale of sheep’. Sea-weed to the value of £20,000 is landed at the quay in Spring, brought in boats “of which from 60 to 100 sometimes arrive in one tide”.

Dr. Archdeacon, the Roman Catholic bishop resident in Kinvara, had successfully overseen the building of a new parish church outside of town, which was completed after his death in 1823. For the Established Church of Ireland, the Rev John Burke of Kilcolgan, was the incumbent, and plans were underway for the construction of a new church in Kinvara that was to stand on glebe land along the new street’ that today runs from the corner of the two-storey hotel on the main street down towards the garda station. Prayers for the Protestant community, in the absence of a church, were read by the Rev. Burke every Sunday in the house of William Dann, a linen draper who was also postmaster from 1844 to 1853.

In the first of the Roman Catholic Parish Registers for Kinvara, which were kept from 1831, there is a valuable list, compiled by the Rev. Thomas Kelly in 1834 of Catholic parishioners. From it we are given some of the occupations practiced by town residents: Pat Leonard, was a schoolteacher and a publican; Michael Divineny, a shoemaker; Matthew Winkle, a carpenter; John Heynes, a boat builder; Pat Curley, who was a butcher and a carpenter; Thomas Whelan, a tailor, Matthew Winkle, a boatman.

In 1838 Kinvara National School opened its doors. This school – the original building, with a plaque over the door dated 1840 – is no longer in use has the distinction of being the earliest school built under the new National School Act.

In 1839 the first comprehensive land survey of Ireland was undertaken by the Royal Army Corps of Engineers, the Kinvara area being surveyed by a Captain Stotherd and Lieutenant Cahytor, under the general direction of Captain Larcom. Dr. John O’Donovan, the learned antiquarian we have several times quoted, had the job of recording all the ancient monuments in every area to be surveyed, as well as to note carefully the Irish names of places in a district; he remarked at the time of his visit to Kinvara the previous year that it was ‘a fast improving little sea-port town’.

Also in 1838 the British Government enacted the Primary Valuation of Tenements Act which had the job of determining the amount of tax each landholder and tenant should pay towards the support of the poor and destitute within its particular Poor Law Union. Sir Richard Griffith was appointed Commissioner of Valuation. This massive country-wide survey took from 1839 to 1856 and its detailed lists of owners and occupiers provides an unparalleled source of information on who lived where in mid-century Ireland.

The Poor Law Union Act, also enacted in 1838, divided the parishes of each barony within a county so as to create Unions to handle the problem of poverty and indigence. Kinvara, Doorus and Killina became part of the Gort Union. It was a timely and even prophetic undertaking. For within less than a decade ‘the fast-improving little sea-port town’ of Kinvara was to share in the social and economic disaster known as the Great Famine.

The last census before the Great Famine in 1841 showed the combined inhabitants of Kinvara and Doorus to be 6,586 persons. The town itself had a total of 959 persons, compared to 385 in 1821. After the Famine both these figures – for the combined parish and the town – steadily declined. While the town was still to achieve during the second half of the 19th century a certain prosperity, the optimism of the pre-Famine years was never to be recaptured. Increasingly, emigration was to be seen as the only way for an enterprising young man or woman to get ahead.

(One of those young emigrants who made a valuable contribution to Irish culture, both through his own songs and ballads and through the work he did in London on behalf of the Irish Literary Society, was Francis A. Fahy. Perhaps best known for such extremely popular songs as ‘The Ould Plaid Shawl’, ‘The Queen of Connemara’, and the original version of ‘Galway Bay’, Fahy was born in Burren, Co. Clare but grew lip in the town of Kinvara in the hotel his father, Thomas Fahy, who was also postmaster, owned and operated (now The Old Plaid Shawl). Trained as a National School teacher, he emigrated to England in 1873 where he worked for the English Civil Service while also writing his songs and lecturing on Irish culture and history.)

The sober language of the Vice-Guardians of the Gort Union presents the picture of the Famine’s impact: “Along the shores of the bay of Kinvara and the bay of Galway…reside a considerable number of persons, some with and some without land, who have heretofore supported themselves by fishing, and by the sale of sea-weed for the purpose of manure. The failure of the potato crop in 1845 and 1846, by its discouragement to the planting of potatoes, completely paralysed the operations of the latter, who are now in a most abject state.

In more vivid and emotional terms, Fr. Francis Arthur described the state of Kinvara to a meeting in Gort on 17th February 1847, telling the assembled members of the Gort Presentment Sessions that they were now burying people without coffins and that the week previously two coffins were buried by day and two by night. Fr. Arthur added that he was himself so exhausted by his attendance on the dying at all times of the day and night that he found it difficult to speak at all.

Dr. Denis Hynes, who was married to a daughter of Captain Theobald Butler of Seamount, in 1847 purchased from his father-in-law the house and larnds. Dr. Hynes was the doctor in Kinvara during the Famine years and evidence shows him to have been tireless in his efforts to deal with the results of famine and fever.

Seapark House, now a ruin standing on the crest of the hill to the east of the town, overlooking Dunguaire Castle, was turned into a temporary fever hospital in March of 1848, and Foy’s Cemetery, a few hundred yards to the northeast of the house, was used to bury the many who died there. Dr. Hynes himself fell seriously ill of fever in 1848 but fortunately recovered. In the 1860’s, however, during a smaller outbreak of typhus, two of his children fell victim to it.

Even when the worst of the Famine had ended, the following decade saw a change of landlords that was to result in continued distress and increased immigration. Sir William Gregory was obliged to sell his portions of his Kinvara estate, including Kinvara which, in the early fifties was reported to be on the verge of complete decay, in the Encumbered Estates Court in 1857, to cover debts incurred during the Famine years. The purchaser of the Kinvara estate was Henry Comerford, a Galway merchant.

Comerford obtained a bank loan in Dublin in order to purchase the Kinvara properties on the strength of the rents which would be obtained once he had gained possession. Unfortunately Sir William Gregory’s retationship with his tenants was such a good one that the question of secure leases had never arisen so long as he was landlord. However, as soon as Comerford obtained possession he proceeded to double and even treble existing rents. The mortgage he had obtained from Messrs Cobb & Moore, a Dublin firm, in order to purchase the property had been arranged on the strength of an increased rental beyond that which had been set by Sir William at the time of the sale in 1857. Now, with no security of tenure, Comerford increased rents drastically

What Comerford acquired in his purchase included the Tolls and Customs, Delamaine Lodge, the area known as Town Parks, the Fair Green, the gate house and the animal pound: in all, a total of 33l acres. It is interesting to note that observations in the rent books of the Kinvara property of Sir William Gregory give a fairly glowing account of the town:

“The lands of Kinvara include the seaport and market town of Kinvara where large quantities of corn and agricultural produce are disposed of weekly, and an immense quantity of seaweed and turf loaded on the quays. Two cattle fairs are held annually and it is contemplated to hold two additional fairs to meet the rising prosperity of the town. The harbour has a good pier and quays and is capable at a moderate outlay of receiving ships of good size and this being the port of Gort, and of very extensive and rich agricultural districts, the trade, at present considerable, must of necessity much increase…Petty Sessions are held in the town and it is a Constabulary Station.”

According to Jerome Fahy, in History and Antiquities of the Diocese of Kilmacduagh, the results were altogether disastrous: “the comparatively short interval of about twenty years witnessed the ruin of over a thousand homesteads in one parish” on Comerford property. Fr. Arthur observed, “The change of landlords for the greatest portion of this place has rendered this one of the most wretched and deplorable parishes in Ireland”. It was, he said, impossible to obtain aid even from the merchants of Kinvara because they, as a result of Comerford’s rackrenting, were ‘bereft of all hope.

By 1866 Isaac Comerford, Henry’s brother, who was a draper and general shopkeeper in Kinvara, was adjudged a bankrupt, and his assets were seized by officials of Todd Burns & Company, Marys St., Dublin for monies owed. As historian Padraig Lane succinctly puts it: “The goose that had laid the golden egg had been killed and had exacted its revenge.”

In 1873 the town saw another change of landlord. The estate of Isaac B. Daly was declared bankrupt and put up for sale by auction in the Landed Estates Court. Daly and his wife had lived for a time in Delamaine Lodge and is mentioned in the Galway Vindicator in 1855 ‘among the good and charitable landlords of the parish’, along with Captain Blake Forster, who had purchased the Doorus Demesne house and estate and later also portions of Kinvara to the west of the glebe lands, Mr. W.G. Murray, who purchased the Northampton estate of James Mahon, and Dr. Denis Hynes of Seamount House.

The description of his property also contains some interesting information about the town in this year. For example, we learn that the corner house, now owned and occupied by Michael Connelly, at the bottom of the main street, was only now being built. From the description of this new dwelling we can also locate the 19thcentury R.I.C. sub-station, which occupied the site of what is now the lounge of the Downtown Bar. Though demolished years ago, the location of the old constabulary is preserved in Barrack Lane, a narrow passageway that runs between two houses on the eastern side of the road that goes to Gort.

Prospective purchasers were also informed that “there Is now on the Bay of Galway a steamer between Galway and Kinvara”. The tenants are described as “industrious and quiet” and rents are paid ‘punctually’. Also it is stated that “there is a body of fishermen in the town of Kinvara”, and these live in what the rent books call ‘the hollow’; this is clearly the Claddagh.

The Estate Map also indicates the site of an old quarry behind what is now behind Garda P.J. Walsh’s house.

The purchasers of the Daly Estate in 1873 were William Henry Sharpe and Henrietta Sharpe (described as a widow and probably the sister of William Henry Sharpe, as their address is given as the same) who paid £13,000 into the Bank of Ireland. It would appear that neither ever lived in Kinvara; this purchase was purely a business transaction and the property was almost immediately leased to Charles French Blake Forster of Castle Forster (what the Blake Forster’s called the old French estate in Doorus Demesne), who also acquired the Tolls and Customs and Fairgreen fees, and Francis O Donnellan.

In 1875 the Sharpes assigned the mortgage deeds of their Kinvara property to Henry Moore of Co. Tipperary, who was the son of Richard Moore and Emma Francis Moore nee Sharpe, clearly a relation of the Sharpes. Another trustee of the settlement was Charles Cobb of Co- Dublin; Cobb & Moore was the Dublin firm Henry Comerford had mortgaged his estates to in 1857.

The ground rents of Kinvara were finally bought by the tenants in the 1940s. From official documents, we see that some, at least, of the people to whom they were paid had the same names we have noted in the 1873 purchase: Mabel Moore, Raheney, Dublin, and Major Richard Stephen Tynte Moore, of Wiltshire, England.

Kinvara’s situation as a port – the port, furthermore, of Gort, the largest town in South Galway, and Loughrea, another large town in southeast Galway – was the key factor in the 19th century development of the town. In fact, the fortunes of the town rose and fell with the fluctuating fortunes of the port.

Throughout the 19th century, and extending into the early decades of the 20th century, large quantities of wheat, barley and timber were exported, and cargoes of turf from Connemara, coal and artificial fertilizers arrived for local merchants like the Flatelys, the Joyces and, later in the century, the Johnstons.

The principal mode of conveyance was the Galway hooker and its smaller sisters, the gleoiteog and the pucan. These sleek, masted boats – extraordinarily graceful as well as superbly designed to travel along the coasts and in the bays and inlets of Galway Bay – carried on a steady trade between Kinvara and places like Lettermullan, Rosmuc, Camus, Mweenish and Sruthan.

Close contacts were built up and marriages often made these connections even closer. We also should not forget that Doorus, which shared in the maritime prosperity, had a good pier on the eastern edge of the peninsula at Parkmore, as well as both Kinvara town and its surrounding townlands, were still largely Irish-speaking throughout most of the 19th century, making for even greater intimacy and familiarity.

From the 1850’s on there was a thriving boat building business in Kinvara, located at the low hill (where Toddie Byrne today has his home) at the bottom of New; or Barrack, Street that was called Cruachan na mBad. Some of the finest hookers still sailing, such as ‘The Lord’ and ‘Tonai’, were built on this site. According to tradition, traveling craftsmen or ‘saors’, in Irish, would engage to build a boat on contract for the prospective owners. ‘Saors’ associated with Kinvara include the Keanes, who were natives of Kinvara; the Brannellys, from Maree; the Caseys and the O’Donnells, both from Connemara.

Once complete, the new boat would be launched into the sea from Cruachan at the big spring tides. Seaweed would be gathered beforehand and arranged as a path for the boat to follow as it was eased down the slippery slope Meanwhile, as the boat began rolling, dozens of men would guide its progress by pushing from every angle until it slid smoothly into the waters of Kinvara Bay.

In 1875 Dr. Denis J. Hynes, who had served the people of Kinvara during the dark days of the Famine and who was held in such high respect by his peers in the medical profession that he was elected at one time President of the Irish Medical Association, of which he was also a founder, died at his borne, Seamount House, on August 16th. Only a month before, Dr. Hynes’ son-in-law, Dr. William Nally, had been unanimously selected as the new Kinvara medical officer upon Dr. Hynes retirement.

Three years later, in. 1878, St. Joseph’s, the newly-built convent and church of the Sisters of Mercy was officially dedicated in an impressive ceremony that was reported at length in the Galway Vindicator. The steamer ‘The Citie of the Tribes’ carried 300 invited guests from Galway. The Bishop, Dr. MacEvilly, performed the dedication and the dedication sermon was given by the famous Dominican preacher, Fr. Thomas Burke. Special tribute was paid to Captain Charles French Blake Forster, who had donated the three acres of land for the construction of the church and convent and grounds, and William Brady Murray of Northhampton House who donated £2,000 towards the costs of erecting the building, and a further £2,000 as an endowment.

Information from the 1894 edition of Slators Directory, a country-wide gazetteer, provides us with a brief but illuminating picture of Kinvara as it moved out of the 19th and into the 20th century.

Kinvara, we are told, is the head of a petty sessional and dispensary district. From the Church of Ireland perspective, the parish was joined to Kilcolgan, and the small church on the New Street was still in existence. The Catholic Church, St. Colman’s, stood a few miles outside the town. The National School stood a few hundred yards to the east of the parish church.

The postmistress was Mrs. Mary O’Donnell and the post office itself was at the corner of Main Street and New Street. Petty Sessions were held every second Wednesday and John Whiriskey was clerk. The Dispensary District Medical Officer and Registrar was William J. Nally, now Kinvara’s doctor for almost twenty years, who lived at Thornville Lodge, on the outskirts of town.

As the new century began, the figures from the 1.901 Census support the earlier statement that after the Famine the town went into a gradual decline, a process that has characterized Kinvara throughout most of the 20th century.

Kinvara town in 1901 had 340 people; there were 106 houses, of which 86 were inhabited. Ten years before, in 1891, there were 384 persons; twenty years earlier, in 1871, Kinvara’s population was 614 persons; ten years earlier, in 1861, there were 980 persons; ten years before that, it’ 1851, it was 1,102; and ten years before, in1841, 959. When we consider that in the first census of 1821 there were 385 people living in the town, Kinvara, eighty years later, had fewer inhabitants – 340 – than it had as near to the beginning of the 19th century as statistics allow us to get.

For more specifics about the house and its modern history, see Modern History of Delamain Lodge.

Original treatise by Jeff O’Connell